From Launch to Landing: How NASA Took Control of Its HTTPS Mission

18F Editor’s note: This is a guest post by Karim Said of NASA. Karim was instrumental in NASA’s successful HTTPS and HSTS migration, and we’re happy to help Karim share the lessons NASA learned from that process.

In 2015, the White House Office of Management and Budget released M-15-13, a “Policy to Require Secure Connections across Federal Websites and Web Services”. The memorandum emphasizes the importance of protecting the privacy and security of the public’s browsing activities on the web, and sets a goal to bring all federal websites and services to a consistent standard of enforcing HTTPS and HSTS.

HTTPS is important for a federal agency like NASA, whose presence on the web is a critical part of achieving our mission of sharing knowledge and information.But NASA is big!

Moving to full HTTPS deployment for NASA represented a significant challenge. We host well over 3,000 public-facing websites and services across 12 geographically dispersed and managerially distinct centers. Communication across such a diverse workforce is difficult and required the concerted effort of a core team in the Office of the Chief Information Officer (OCIO), representatives from each of the centers, and systems administrators from across the agency.

However, by May 2017, after several months of working through these challenges, NASA was able to reach over a 95 percent compliance rate.

NASA’s success hinged on a few key aspects, all rooted in clear (and frequent) communication and teamwork. What follows are some of our strategies and lessons that we learned.

Leadership buy-in

At NASA, geographically dispersed centers operate largely independently and with distinct senior leadership teams. These teams are overseen by the NASA OCIO, which, in June 2016, established a core team to oversee HTTPS compliance tracking activities. The OCIO additionally issued guidance on the importance of meeting the HTTPS-Only standard with an action to each center Chief Information Officer to delegate an accountable center representative to oversee further activities. This first tier of delegation was essential to engage the right stakeholders. The center representatives subsequently tasked technical representatives from the various systems in their purview. This multi-stepped delegation of responsibility represented the agency’s commitment to improving HTTPS compliance at the highest levels, and helped establish clear communication channels all the way to the people responsible for actually making the necessary system-level configuration changes.

Leadership at the agency level further demonstrated support of the HTTPS deployment efforts by issuing progressive guidance on the use of Let’s Encrypt and associated Automated Certificate Management Environment (ACME) clients for certificate issuance and management.This was a big deal!

Early on, the agency core team decided to publish an agency white paper after realizing that a large number of commercial certificates would need to be provisioned (at great expense) to address various barriers to compliance. To make the imminent onslaught of Let’s Encrypt certificate requests possible, NASA had to negotiate a rate limit increase with Let’s Encrypt for the nasa.gov domain, assess the popular ACME client Certbot, author and publish the white paper, and establish a platform for sharing recommended best practices and sample configurations with system administrators.

The benefits were clear, though. Not only was Let’s Encrypt a more cost-effective option, it pushed NASA towards automated management of certificates and demonstrated the agency’s support of modern technologies.

As NASA approached full HTTPS deployment, stragglers became evident, primarily with commercial products that could not support certain technical configurations. NASA leadership coordinated conversations with vendors and technical experts from NASA, where the teams could have in-depth conversations about the HTTPS-Only standard. For many vendors, OMB’s HTTPS policy was news to them! Collaborating with industry partners proved to be critical to success and will hopefully generate benefits for other agencies.

Finally, for those few remaining unresolved stragglers, NASA developed an internal waiver process. Any submitted waivers had to address technical constraints and detail firm timelines for remediation. Most importantly, responsible stakeholders were required to present their arguments and obtain approval by the agency Chief Information Officer and Chief Information Security Officer in a face-to-face meeting. Involvement of agency leadership at this fine-grained a level was generally unprecedented and really enforced for the community the importance of the overall effort.

Tiered and tailored communication

In total — counting the agency core team, center delegates, and system administrators — the stakeholder community for HTTPS compliance efforts was well over 100 individuals. Each subgroup within this community was concerned with different aspects of the HTTPS deployment efforts, and required information to be delivered in different ways.

To address the entire community, the agency core team stood up multiple communication channels:

- An agency source control repository for storage of recommended configurations and tool implementations

- An internal agency blog for posting responses to frequently asked questions and pertinent knowledge articles

- A “hotline” mailing list where stakeholders could request support from the agency core team regarding spot check scans and general troubleshooting

- A weekly meeting for the core team to discuss overall progress, ongoing problem systems, and upcoming milestones

- Regular waiver review meetings, wherein the agency core team would assess the completeness of waiver submissions and provide feedback to requesters

- A weekly meeting for center representatives to discuss progress and voice any pressing questions and concerns. Systems administrators would often also phone into these meetings if there were technical issues that were pertinent to the larger community.

- Targeted group meetings with systems administrator teams, center representatives, the agency core team, and occasionally vendor technical support. These meetings occasionally would result in vendor teams taking actions to develop remediation plans for their products; as these vendors were often serving multiple federal agencies, the impact could be significant and of broader benefit than just to NASA.

One pertinent lesson: The core team underestimated the volume of communication through the “hotline” mailing list, as well as the similarity of discussion across multiple disparate threads (there was lots of text snippet cut-and-pasting). Moving forward, as the agency shifts focus to non-public networks, use of chat channels and more dynamic platforms for communication may be more useful.

Tool and reporting consistency

Regularity and consistency of communication across the diverse stakeholder community was an important part of NASA getting compliant.

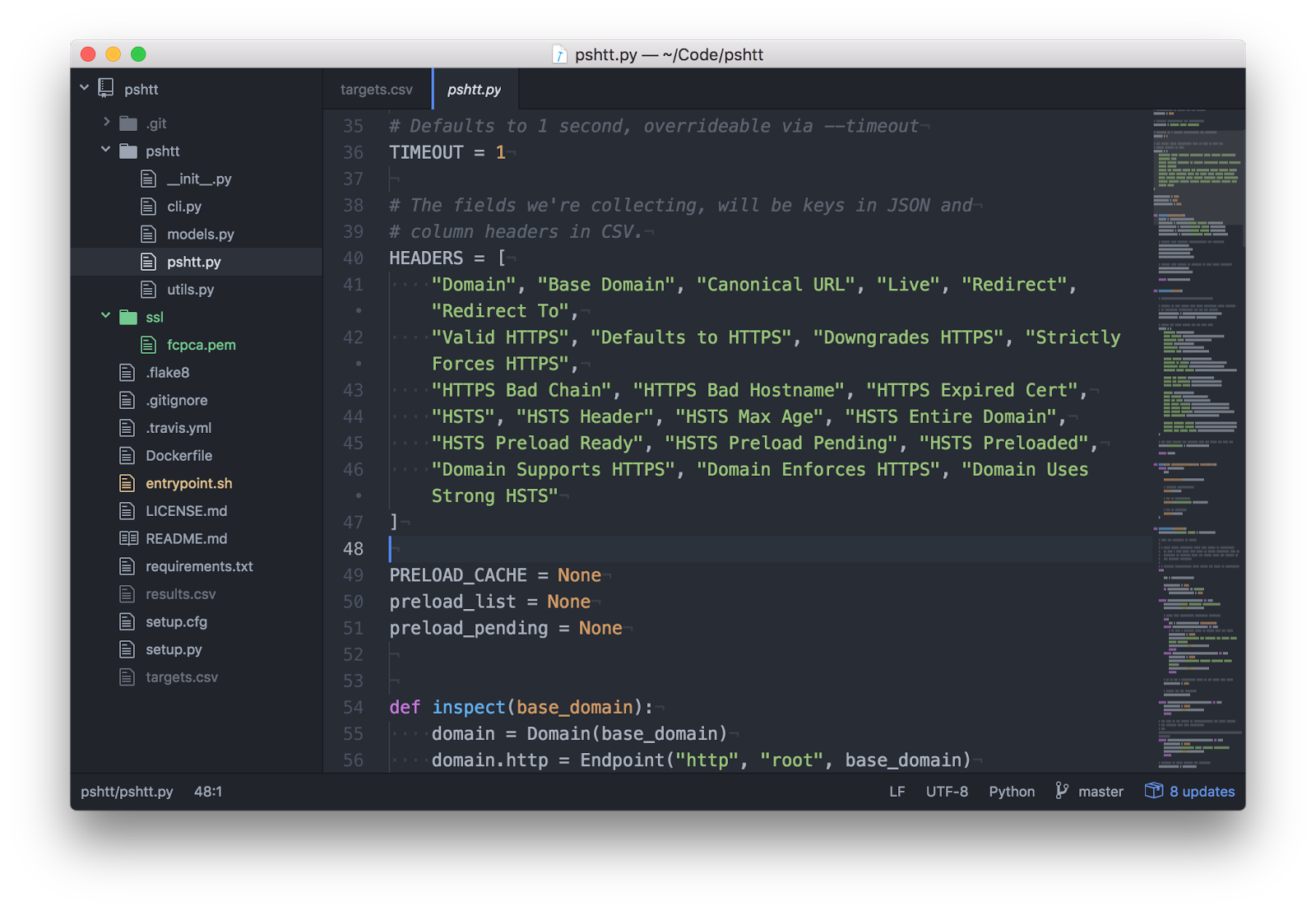

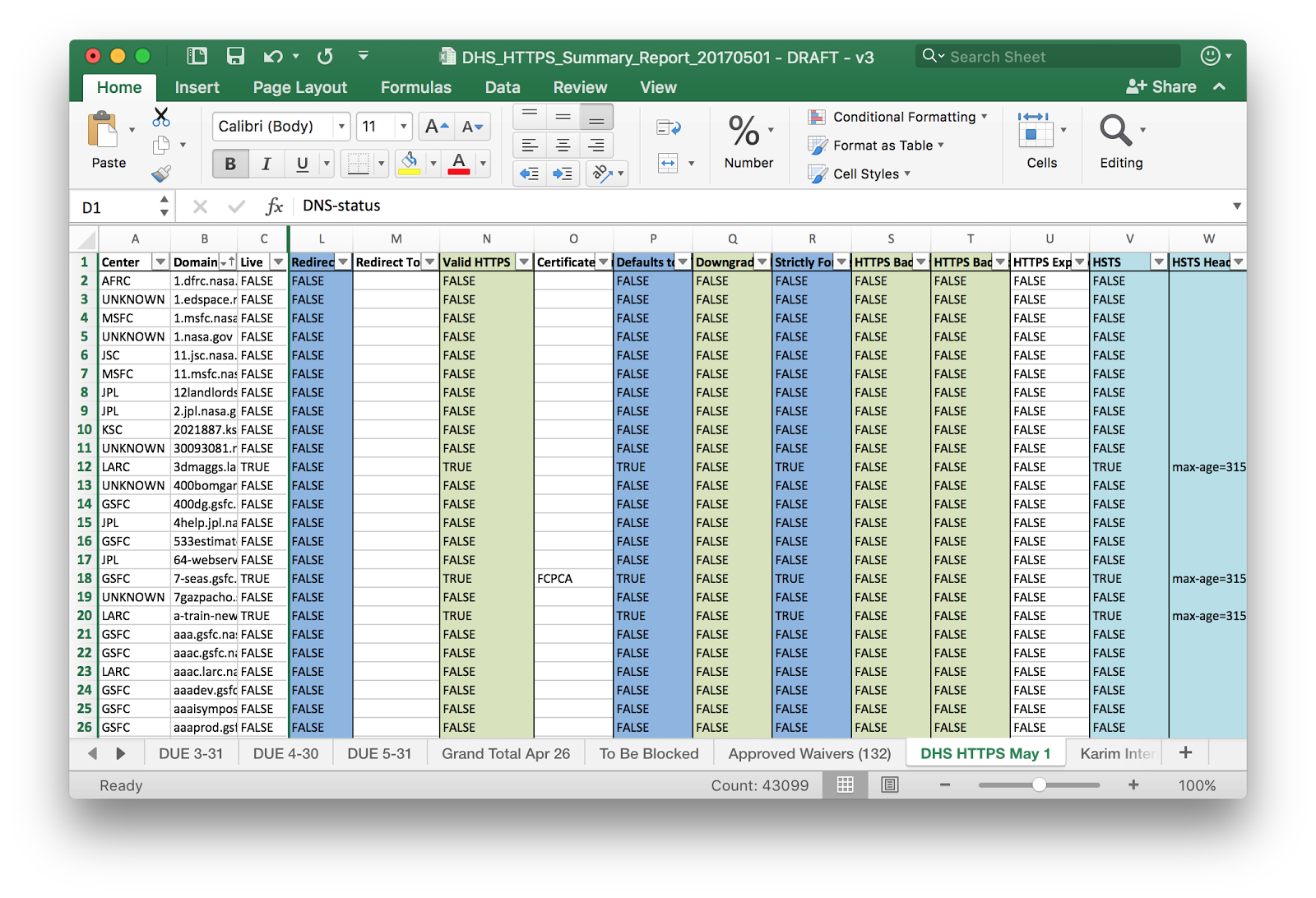

For NASA, tool selection began with delving into use of pshtt. The Department of Homeland Security and the General Services Administration both use pshtt to scan agencies, and collaborated in its development. NASA found a lot of benefit in studying pshtt and came to really value the insight provided through the tool’s open source development. Beyond vanilla pshtt, we augmented the tool’s output to map responsible centers to target websites and services for easier communication to stakeholders, and even contributed to the tool’s overall development.

We also augmented reports to track targets longitudinally, monitoring for endpoints that disappeared or changed between scans. This sort of analysis was helpful for one-on-one troubleshooting, which the core team supported by offering spot check scans for system administrators that were unable to run pshtt independently. For these purposes, the agency core team maintained a troubleshooting branch off of the canonical pshttmaster branch to support checks with multiple timeouts to account for many of NASA’s high-latency targets, and to use an augmented trust store that included the Federal Common Policy CA.

In addition to pshtt, NASA used other common applications, such as curl, OpenSSL, and Nmap, and included their output alongside results from pshtt.

Finally, NASA combined HTTPS compliance findings with a TLS cipher usage audit. These cipher reports were driven mainly by NIST SP 800-52 and certain findings from DHS Cyber Hygiene activities (especially SWEET32 vulnerabilities stemming from known weaknesses in 3DES ciphers). In a similar spirit to pshtt, the code used to audit ciphers was made available for collaborative development through an agency source control repository and used to generate regularly scheduled reports.

Challenges

The core team identified some difficulty among staff in grasping the spirit and the letter of OMB’s HTTPS policy, M-15-13. Specifically:

- There was a lot of resistance to enabling HTTPS for an HTTP service that simply redirected to another site. Over the course of NASA’s history on the web, the agency has created numerous URLs that have subsequently either fallen under other groups or ended up in print.

- Similarly, enabling HSTS on a service that only redirects to another endpoint was questioned consistently, as was enabling HSTS on a server that never offered plain HTTP.

- Even the definition of “web server” was sometimes contested, with many stakeholders debating that a listening service which did nothing but (purposefully) respond with an HTTP error code and did not provide traditional web content (for example, HTML, CSS, or JavaScript) did not qualify.

To resolve these cases, we reviewed the spirit and letter of OMB’s HTTPS policy, M-15-13. All of the questioned cases are certainly in scope, and NASA contributed edits to the guidance on OMB’s HTTPS-Only Standard website, to help clarify. This all contributed to our system administrators moving towards compliant implementations.

Ever onward!

Although NASA has made significant improvements to HTTPS and HSTS deployment to our public web services, we’re excited to get to work on applying the same technical rigor to our internal services. Additionally, NASA intends to eventually preload the *.nasa.gov domain, fitting into the larger federal government effort to preload federal .gov domains by default.

But most importantly, NASA looks forward to further collaboration with our federal and commercial partners. Privacy and security are complex problems, but the lessons learned through efforts like meeting the HTTPS-Only standard teach us how to make them surmountable. These challenges require coordinating smart minds at work across our government. By continuing to work together, NASA sees the potential to make important changes for the benefit of all.This post was originally published on the 18F blog.