From Elephant to ELK: How We Migrated Our Analytics System to Elasticsearch

As I mentioned in a recent blog post about image search, we’re avid users of Elasticsearch for search. We also recently ported another vital part of our system to Elasticsearch: analytics.

This post is a technical deep dive into how our analytics system works, and specifically how and why we used Elasticsearch to build it.

Background

DigitalGov Search is essentially one giant software-as-a-service (SaaS), with 1,500 government websites as its customers. Each site, in turn, is a resource for the public to use. To help us understand how people use the search box and how we can make it better, we collect quite a bit of data. Some of that data makes its way into data products, automatically improving future searchers’ experiences. Some of it helps us keep track of the health of the system, alerting us to issues and anomalies that might impact searchers. And all of this data helps us answer ad hoc questions, support hypotheses, and back up intuitions we have about how the service should evolve. It even populates an engaging real-time dashboard we have running on a monitor at GSA, reminding us of our commitment to improving each individual’s interaction with government.

What We Store

Searches: We collect data on what people search on, when they searched, what site they searched from, what we showed them for results (e.g., news, images, recommended content), and various other bits of information to give us context on the search. We can also see trends for searches about certain topics, like jobs or health care for example. That means even our analytics system has a search aspect to it, albeit a very different one than what individual searchers experience through the search box on .gov sites.

Clicks: Ideally, a searcher will find a relevant result and click on it. In addition to collecting data on the clicked URL, we log the position of the result and the type of result that got the click (e.g., a tweet, YouTube video, etc).

Pageloads: When available, we collect pageload information and use it to show customers what pages are popular or trending on their site, and we also use it to inform our own rankings on search results pages.

Errors: The vast majority of the time, the whole system hums along nicely. But when errors pop up, we keep track of them so they’re easily accessible without having to log into servers and comb through log files.

The Hadoop Years

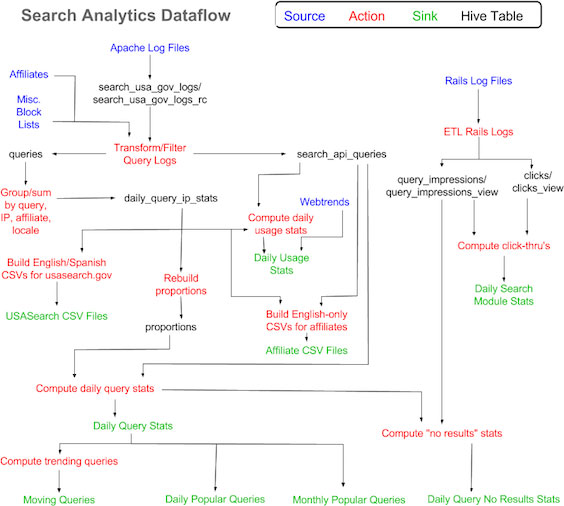

Our program has had an analytics need for longer than Elasticsearch has been around, so we’ve had different solutions in place over the years, all of them based on open-source software. Looking back, it seems like we had little more than stone knives and bearskins to work with when we first got started. Everything was built to run on a single machine, and we had to jump through all sorts of hoops to process and store even a few weeks of data. Most recently, we used a combination of Hadoop, Solr, and MySQL to build out our analytics pipeline. The Hadoop Distributed Filesystem (HDFS) solved the storage problem for us, as we were able to easily expand our capacity and redundancy just by adding more disks. MapReduce proved to be a good solution to our processing problem by letting us use multiple machines to operate on our ever-growing amounts of data, but MapReduce is a batch processing system, and some of our information needs required a low-latency solution.

We used MapReduce to aggregate the most important data into manageable representations that could fit into our database and get exposed through our Ruby-on-Rails-based admin center, where we built out simple graphs and charts with existing front-end libraries like Google Charts. By indexing some of the rolled-up data on search terms in Solr, we were able to quickly see trends around, say, internships by including different search terms like summer intern jobs and paid internships. The whole thing had a bit of a Rube Goldberg air to it, but it was a much better solution than its predecessor. Moving from a single-node solution to a distributed system relieved our anxiety around growth but at the same time, it introduced a lot of complexity.

For one thing, there were quite a few instances of the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) making up the different components of our Hadoop cluster, including the Name Node, Secondary Name Node, Data Nodes, Task Trackers, Job Tracker, Balancer, Hive Metastore, Hue, Flume, Oozie, Zookeepers, and Solr. We had a lot of moving parts, and each one needed to be monitored for availability, occasionally patched or upgraded, and so on. And while we now had scalable storage and computation, we didn’t have any easy ways to visualize what we discovered. Nobody liked taking the results from an ad hoc Hive query and pasting it into Excel just to generate a chart.

Around that time, we started experimenting with Elasticsearch as an alternative to Solr for some of our public-facing search indexes, and we were really impressed with its operational simplicity, feature set, community support, and development velocity. Several of our colleagues recommended the Elasticsearch core training class as a good way to ramp up our knowledge quickly and get the most out of the product. In separate classes on two coasts, we were surprised to see how many people were using Elasticsearch solely for analytics, not search, and they were using Logstash and Kibana alongside it for data ingestion and visualization, respectively.

One colleague asked, “Couldn’t you just store every single pageload, search, and click in Elasticsearch via Logstash and just query and visualize it all in real-time with Kibana?” This seemed ludicrous for so many reasons. How could Elasticsearch aggregate across all of that data in a few seconds or less while applying arbitrary filters across potentially a dozen different fields? And let us examine pageloads, searches, and clicks across any timeframe all in a single query? And then let us compose complex dashboards—without any programming—that somehow reflected events in near real-time? And be able to drill down to the original event in its original fidelity, not some higher-level rolled-up approximation?

The ELK Era

The notion of using Elasticsearch for some of our analytics kept popping up, but we were still skeptical if it could handle aggregations on a high-cardinality field like search terms. This is just a fancy way of saying, “Can it group all the search requests based on the search terms?” The “high-cardinality” part just means that people type a lot of different things into search boxes, and the distribution of search terms has a very long tail. For example, let’s say we had the following searches:

- jobs

- jobs

- ufo’s

- jobs

Aggregating them would go like this:

- jobs: 3

- ufo’s: 1

Now, aggregating 4 searches into 2 groups is trivial and any database can do it. Aggregating 1 billion searches into 500 million groups is considerably harder, which is why we went down the Hadoop road in the first place. The MapReduce model is perfect for this sort of job. Our needs fell somewhere in the middle, and we figured the best way to tell if Elasticsearch would break would be to load up a representative amount of data and, well, see if it broke.

Logstash

Our search, click, and pageload events all get logged in different places in different formats, and each server creates a logfile per day. This turns out to be a perfect scenario for Logstash, which creates an Elasticsearch index per day by default. We created a Logstash configuration file with the basic logic we needed to extract, transform and load (ETL) the search, click, and pageload events into Elasticsearch. We also created an index template for Elasticsearch to use when a new day’s index needed to be created. Most of our data fields are used as simple filter fields (e.g., site ID, module ID’s, search vertical) so the default mapping for a string field is to leave it unanalyzed with no stemming, stopwords, etc. We have a geo_point field for cases where we have geographic information. The search term gets analyzed with the Snowball analyzer, which is more aggressive than the analysis chain we use in our user-facing search products but gives analysts better recall, albeit at the expense of occasionally surfacing irrelevant results to them.

Logstash is definitely not the fastest way to get a lot of historical log data into Elasticsearch, but doing so exposed a lot of gotchas around UTF-8 encoding issues, missing fields, and general throughput tuning, and it helped us make the ETL process more robust for all the future data we’d be “logstashing”.

With multiple Logstash processes ingesting multiple directories of historical log data on each machine, we wanted some feedback on how everything was running. The default Logstash dashboard in Kibana was perfect for visualizing the progress at a glance as each day’s data filled up across the hours. Marvel, a cluster monitoring tool for Elasticsearch, showed us the current indexing rate for each day’s index, and also helped us keep track of dozens of other system-level statistics so we had some before/after measurements on JVM heap usage, CPU, field data cache sizes, and so on.

Performance

We took a handful of the most common analytics queries we tend to run and created versions of them using the Elasticsearch query domain-specific language (DSL). To make sure we didn’t have anything else in the way that might impact performance like a Ruby runtime or a visualization layer, we ran the queries directly in the Sense console. Starting with a small date range and small aggregation size, we iteratively ratcheted up the time window and the aggregation sizes while watching both the query response times and the various metrics that Marvel was reporting. The performance was astonishing and barely degraded as we searched and grouped across millions, tens of millions, and hundreds of millions of records. We got far enough into the experiment to convince ourselves that whatever problems we might run into, performance and scale would probably not be the first ones.

Downsides

Our analytics system based on the inverted index of Elasticsearch/Lucene is fundamentally different from the one we had based on the MapReduce programming model and HDFS, and we had to give up a few things to get there. The Hive data warehouse provided a familiar SQL abstraction layer on top of MapReduce to let us query our data basically the same way we had been querying it when it lived in a relational database. Several people in our organization had enough SQL fluency to run ad hoc queries on datasets in Hive. The Elasticsearch query DSL on the other hand evolved around information retrieval, not relational algebra. Migrating our Hive/SQL queries to the Elasticsearch query DSL took a bit of work, and learning all the nooks and crannies of the rich DSL is an ongoing process, especially as the it continues to evolve. No doubt we will see SQL-over-Elasticsearch libraries for people who don’t need all the expressiveness of the Elasticsearch DSL just as Hive opened up the power of MapReduce to people who didn’t need all the flexibility of writing their own batch jobs in Java.

There are other limits to consider with Elasticsearch. We can’t easily generate enormous output sets as we could with Hive/MapReduce. Taking a billion row Hive table and applying some transformation to it on its way to becoming another billion row table was a simple Hive/SQL command. With Elasticsearch, there’s much more work to do. Our use of filtered aliases (see below) conveniently relieved us of this need, but it’s still a trade-off.

Upsides

Quite simply, under the hood Elasticsearch and the data structures it uses are a particularly good fit for our use case. Maintaining separate bitsets for each field and then using those to find intersections means we don’t have to query the data in a particular way in order for the query to be fast, as we would with a tree-based data store. With MapReduce we didn’t have to query the data in a particular way either, but in that case we were scanning over all the data regardless of which attributes we filtered against. No matter what kind of needle we wanted to find in the haystack, we still had to look through the whole haystack or at least some date-based partition of the haystack. And in our case, we had quite a few of these haystacks.

Our original log data started out in one Hive table and made its way through a cascading series of transformations, additions, subtractions, enhancements, and so on until it ended up in a variety of low-latency data products. Each step of the way, what were essentially successive materialized views would get created either in Hive or in MySQL. Each one consumed storage (albeit not the biggest expense these days, but it adds up). Each link in the chain depended on the prior link, so failures required quick detection and remediation. Testing this pipeline jungle was very difficult, causing technical debt to pile up.

In our new system, an original log entry gets inserted as JSON into Elasticsearch, and instead of going through a pipeline of intermediate stores it gets assigned various tags and decorated with additional fields (e.g., a geo_point) by the Logstash ETL script. Some of the labels we apply to traffic can only be applied after the fact, perhaps after another hour or a day has elapsed, because we have to consider the entry in a larger context. Perhaps after an hour the entry is classified in one way, but after another hour’s data our algorithm might classify it in another way. Rather than repeatedly re-classifying (and re-indexing) the original entry with some tag or another, we use Elasticsearch’s filtered aliases to effectively change the lens we use to see the data. What used to be a fairly heavyweight multi-step process became an atomic operation that required neither changes to the underlying data nor the creation of intermediate tables. In database language, we replaced materialized views with non-materialized views. Even though these aliases comprised thousands of filter criteria across many attributes, the query performance didn’t suffer at all. Best of all, with all the machine resources we freed up from fewer versions of the data consuming disk (both Hadoop and MySQL) and fewer JVMs consuming RAM and CPU, we were able to reallocate some of our hardware to the Elasticsearch cluster giving it even more capacity to scale and perform. This turned out to be very timely, as the “K” in “ELK” brought on a lot of new use cases.

Many modern analytics systems focus solely on the distributed collection, storage, and computation of data, leaving the last mile of visualization as a problem for others to solve. The Kibana component of the ELK stack treats visualization as a first class citizen by exposing the Elasticsearch data through an intuitive interface where complex dashboards can be composed and shared largely via mouse clicks by people who have domain expertise but not necessarily any background in querying data. Showing our analysts Kibana with a little data made them want Kibana with a lot of data, and exploration became a lot more productive and fun for them when they got to hold the flashlight.

Next Steps

The development velocity of the ELK stack nearly outstrips our ability to take advantage of all the new features as they come out. While we continue to build out new functionality in our core search and analytics services, we’re really excited about the prospect of opening up access to Kibana to the customers behind our 1,500 sites, and maybe even beyond that. To that end, we’re keeping a close eye on Elasticsearch’s new Shield product, which is still under development. Opening up secure, measured, audited access to various subsets of our data will effectively give a lot of our customers their own flashlights. These many eyes will find bugs, discover insights, suggest features, and ultimately help us provide a better service to them and to the public in the years to come.